How I think about the Central Governor Model

The Central Governor Model is frequently mentioned in the Moxy Forum. I find this to be a pretty significant concept to grasp, so I wanted to share a few thoughts on how I think about it.

The term “governor” comes from a device used on engines to limit how fast they run. The governor was originally designed to automatically restrict the fuel supply when the engine started spinning too fast. Two balls spun around at the same speed as the engine, and when the engine spun faster, the centrifugal force on the balls would push them apart and activate the linkage to close the throttle. The purpose of the governor was to prevent the engine from damaging itself by spinning too fast.

As my colleague Stuart noted in a recent post on the subject, Archibald Hill seems to be the first one to propose that a similar process might occur in human physiology. His popular quote from 1924 can be found here. Then the idea seemed to sit on the shelf until it was suggested again by Timothy Noakes in 1997. You can read about some of Noakes ideas here (Not the same light reading as this blog post).

When applied to physiology, I understand the basic concept of the central governor to be that the human body has feedback mechanisms which prevent it from exercising so hard that oxygen levels in the heart, breathing muscles or brain would fall to dangerous levels. The governor in an engine is very simple. Engine RPMs are used to adjust the throttle valve position. The governor in a human body, on the other hand, seems to be more complex that just a single input like RPM.

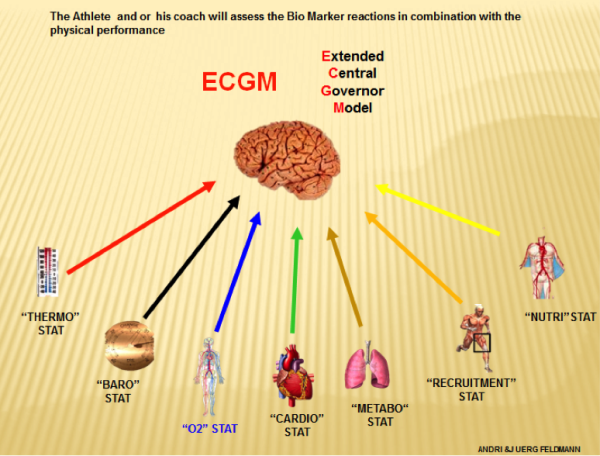

I copied the following diagram from Juerg Feldmann. It does a good job of indicating how the body’s central governor tries to keep many systems in balance simultaneously.

The mechanisms used by the body’s central governor to limit performance are also more complex than any analog of a single throttle valve position could reflect. The easiest physiological mechanism for me to conceptualize is that of the governor causing the central nervous system to restrict the number of muscle fibers which can be recruited in the arms and legs.

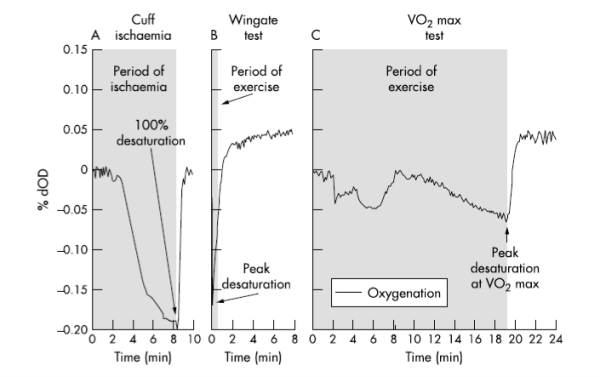

I think one of the easiest ways to see the central governor in action is to look at Figure 4 from the Noakes paper linked to above, which I've added here.

With ischemia and a Wingate test, the working muscle oxygenation drops to very low levels. This is very likely a factor in performance limitation. However, with the VO2 max test there’s still plenty of oxygen in the working muscle when the athlete’s performance reaches its limit. It’s easy for me to conceptualize that in this case the body had some mechanism which shut down the arms and legs in order to prevent damage somewhere else - i.e. a central governor.

You can see similar examples from the following Moxy data: