Case Study: Autoregulation for Sprint Intervals

While science does a great job of measuring the statistical norms of a population, the individual physiologic response to training must be taken into account in order to maximize an athlete’s performance potential. Training autoregulation is the concept that training should be monitored and manipulated on a daily basis, based on the individual physiologic responses of the athlete. In the last blog post I introduced the concept of autoregulation and how monitoring skeletal muscle oxygenation levels via NIRS could provide useful insights to how an athlete is coping with a workout. In the next couple of posts I want to walk through the analysis/real-time monitoring of an athlete completing a repeated sprint style workout, and a lunge based body weight strength circuit.

The first workout I want to walk through is a repeated sprint workout. The main goal of this workout was to assess how an athlete dealt with repeated desaturation/maximal sprint intervals as well as push their repeated sprint capacity. It was important for the athlete to maintain proper form so full recovery was used to dictate rest intervals between each sprint. Here is the workout:

Warm-up

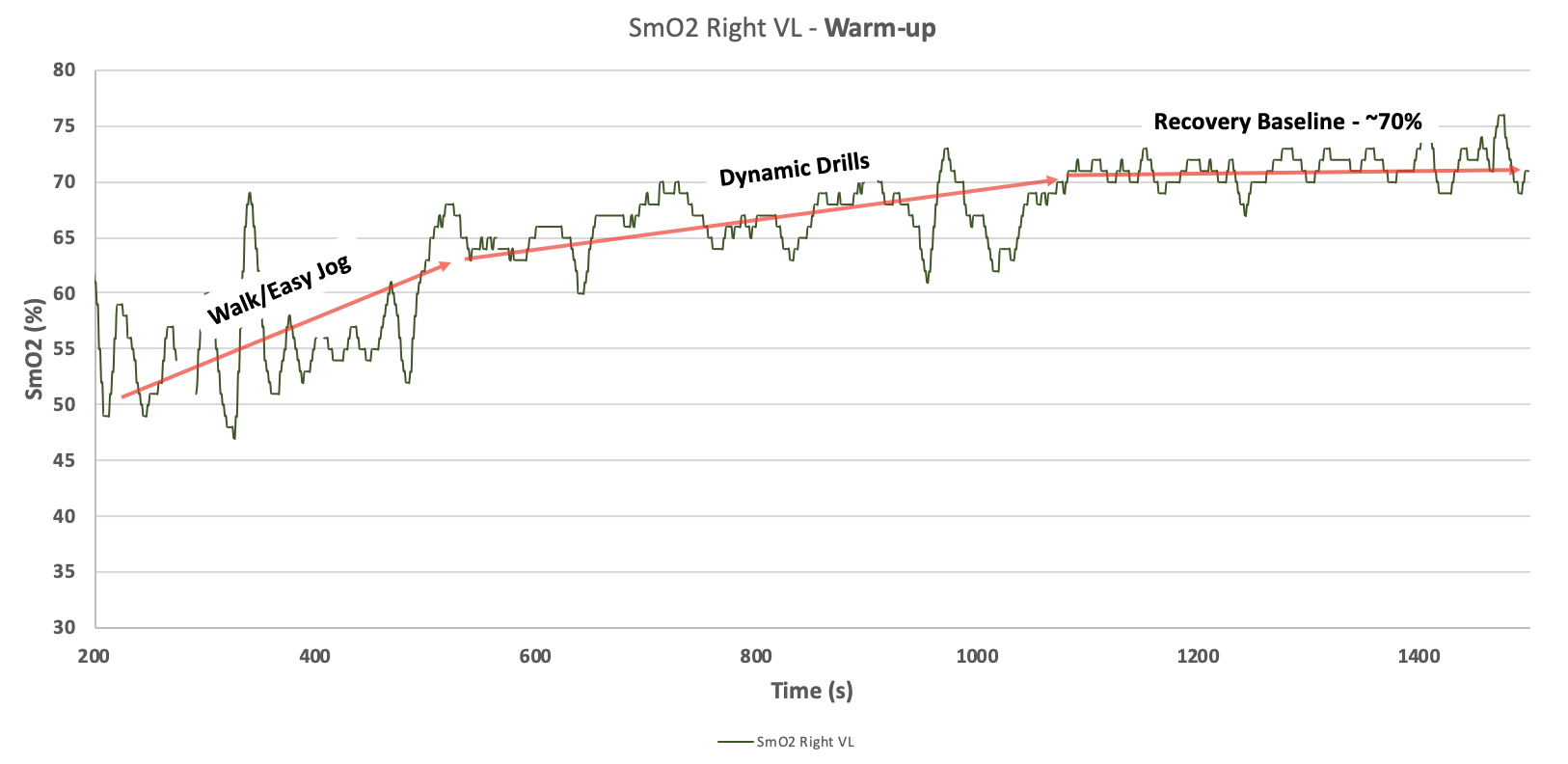

Easy walk/jog: raise SmO2

Dynamic Drills: further raise SmO2 through heart rate increases

Workout

3 Glide intervals: (athlete ran 50-70 yards starting easy then accelerating throughout the interval to ~80% max speed) – This was used to push SmO2 low, which upon rest hyper responds. Rest until recovery baseline.

10-20 x 50yd sprints: Sprints based on the ability to de- and re- saturate. The goal was to hit between 10-20 and not lose any speed in the process.

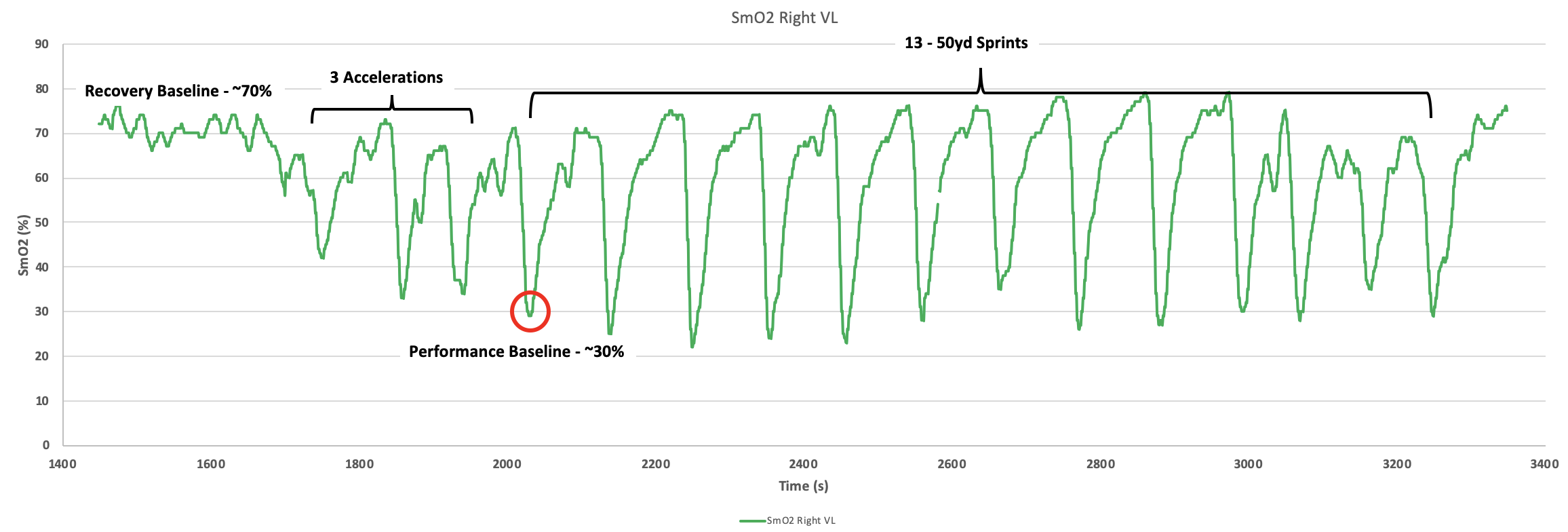

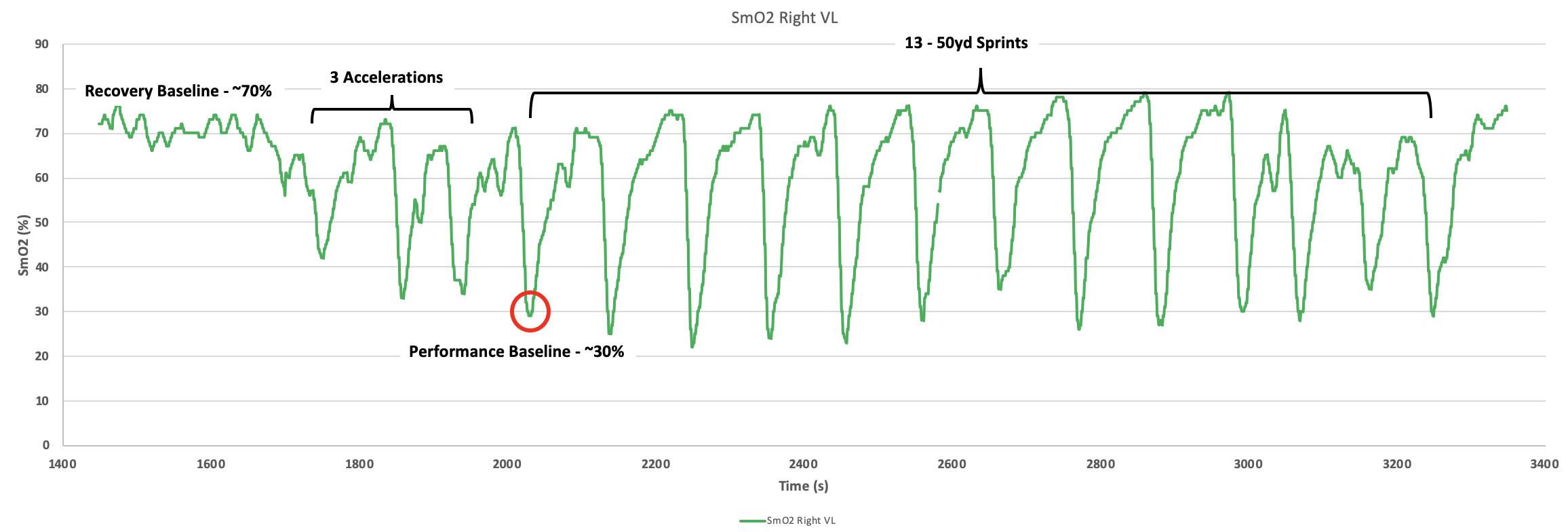

As a coach the first thing to do when monitoring an athlete’s SmO2 is to establish a recovery and performance baseline. The recovery baseline is the SmO2 value that is established after a proper warm-up. From figure 1 it was determined that recovery SmO2 was ~70%.

The performance baseline is the level of SmO2 reached during the first couple of true intervals. From figure 2 the performance baseline was determined to be ~25%.

The next thing for the coach to do is establish what sort of physiologic responses are expected and the end criteria for the workout. For this workout we did not want to overtax the athlete, so the criteria for ending the workout was as follows:

-

-

- If the athlete could no longer reach recovery baseline for 2 consecutive intervals.

- If the athlete could no longer maintain their top end speed for 2 consecutive intervals. For this athlete that means they need to maintain 7s +/- 1s for 50yds. This was determined after the athletes first interval which was completed in 7.4 seconds.

- If the athlete could not desaturate to performance baseline 25 +/- 10% for 2 consecutive intervals.

-

The logic behind the stop criteria above is as follows. In this workout we wanted to push the athletes’ sprint ability (small conditioning effect) while having them maintain good sprint form and speed, therefore we chose to allow the athlete to recover to 70%. This means that the athlete would walk after each interval until their SmO2 hit 70 or above for the first time then they would start their next interval. This would give the athlete just enough time for full recovery so their form/speed wouldn’t be hindered but the rest was short enough 1-1.5 minutes so their heart rate was still elevated at the beginning of each interval (data not shown).

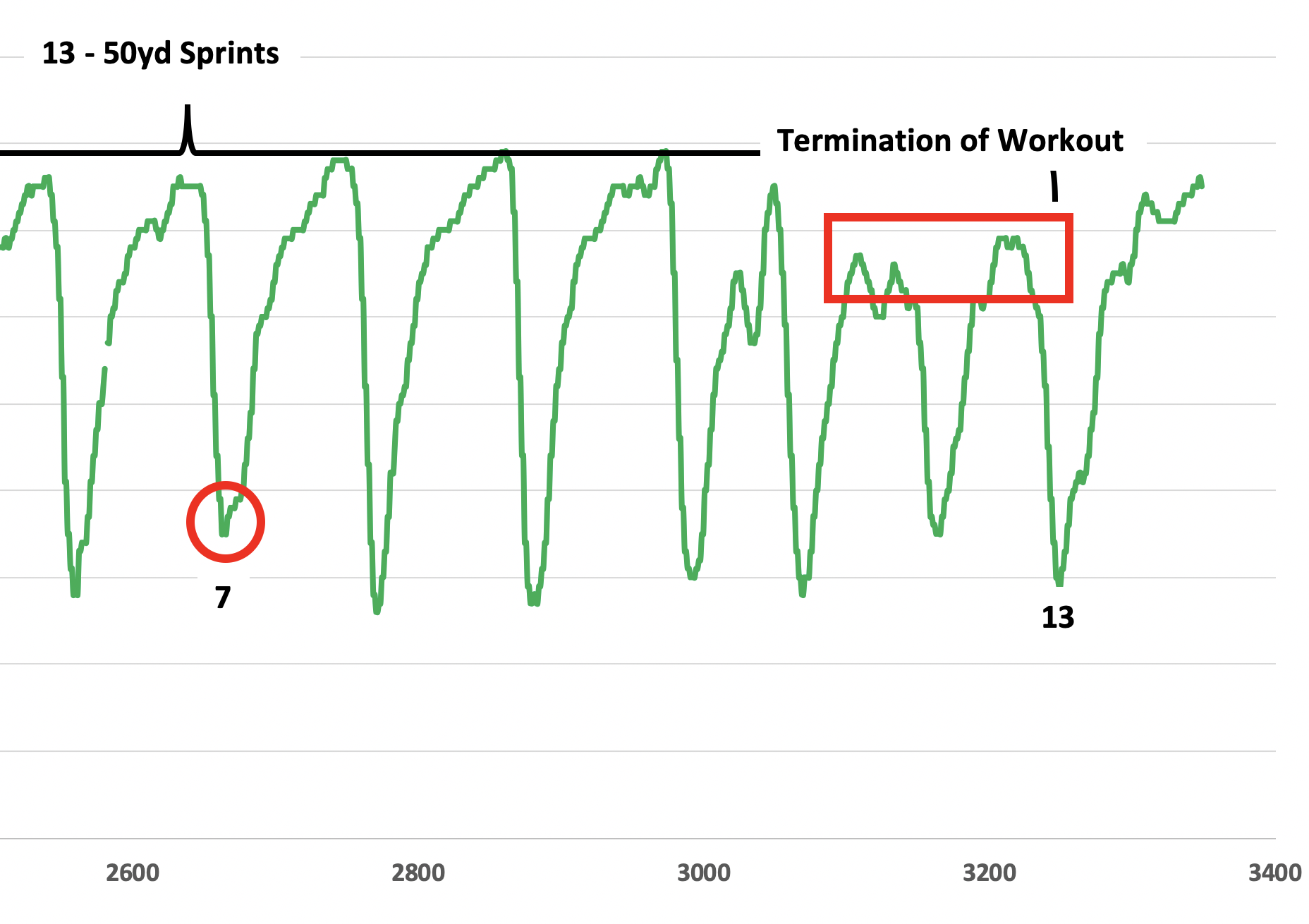

Finally, let’s walk through the termination of the workout. Remember, we set three rules for stopping the workout based on the athlete’s physiology or some performance metric. The first time one of the rules is broken was during interval 7 (SmO2 only reaches 35%) (circled in red on figure 3, below). However, after a little extended rest, SmO2 is able to drop back to below 30% on the next interval. The reason why the workout was terminated after 13 intervals was due to a lack of resaturation (<65%) during the final two intervals (highlighted in the red rectangle, below), the lack of resaturation during intervals was followed by a concomitant inability to desaturate (albeit not outside of our termination criteria). It should be noted that at this point in the workout the athlete was still hitting the same speeds, but their form was beginning to breakdown.

To summarize, this was a workout that was dictated purely by how an athlete was responding to their workout. In order to use SmO2 to dictate a workout recovery baseline, performance baseline, and the selection of termination criteria must occur. Once these three variables are determined, it is the coaches or athlete’s responsibility to terminate a workout when the athlete’s physiology is no longer responding adequately to the workout prescribed. In the next post, I will walk through an example of how SmO2 can be used to monitor circuit/conditioning training.